Lifestyle Column: 10 Neat Things

This week: 10 neat things about Dutch elm disease.

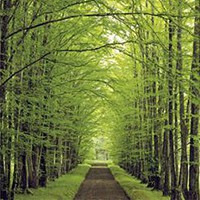

1. The elms. Lining the streets, their great arms reaching toward the heavens, the mighty elms grace our cities with their canopies of green. They break the wind in winter and breathe oxygen and cooling moisture into the atmosphere in summer. They clean up carbon dioxide from the air and heavy metals from the earth. They slough off salt and stoically accept the insult of grievous injury from cars and machinery. They survive the assault from construction excavation which cuts their roots. They will graciously give us back shade for as long as 300 years, if we let them.

2. The beetles. Hylurgopina rupifes and Scolytus multistriatus need elms to live. The first beetle, H. rupifes, is native to North America and in winter it takes up residence in the lower four feet of the elm tree where it snuggles into the bark to survive quite happily until spring. Scolytus multistriatus, the smaller European beetle is not as tough as the native and many populations will be killed off in very cold weather, which is why they look for piles of elm firewood to hide in through the cold months. Don't store elm wood.

3. The fungus. Ophiostoma ulmi feeds on elms, or more precisely, on the inner tissues in the cambium layer under the bark of the tree. It works almost like an auto immune disease in humans; the tree reacts to the infection by trying to block the spread of the disease by producing gum and tyloses (bladder-like growths) in the xylem. The xylem is the mechanism whereby water is delivered from the roots to the body and leaves of the tree. This plugging mechanism cuts off nutrients and water to the affected area, killing it.

4. The carriers. The beetles in and of themselves do not kill the trees. However, they are carriers of the deadly fungus that does. All the beetles want to do is to find a weak and friendly elm in which to mate. Chemically engineered to find likely targets by smelling them on the wind, the beetles are very good at detecting freshly cut wood and damaged or dead wood in which to mate and lay their eggs in galleries beneath the bark. However, they feed on living tissue in the crown of healthy trees for a few days, then fly back to the dying or weakened elm to tunnel and lay their eggs. This brief encounter is all it takes for a new tree to be infected.

5. The symptoms. The first sign is green wilting leaves. It may look as though a few twigs in the crown have been damaged by wind or an animal. As summer progresses, the wilted leaves turn yellow then brown and continue to cling to the tree. Then the damage spreads rapidly, killing young trees in a single season. It may take a year to two to kill an older tree. If the infection can be detected early enough, when less than five per cent of the crown is infected, there is still hope for the tree.

6. The treatment. Before cutting down the suspected tree, call an arborist to check for DED. If indeed the tree is infected the affected branch should be pruned at least 10 feet below the damage. The tree can then be inoculated with a fungicide. The one most often mentioned as being effective is called "Arbotect" which is injected into the root flares of the tree. However, you will need to repeat this procedure every two to three years. The fungus is very hard to eradicate and spreads quickly.

7. Beetle habits. Why are the beetles attracted to weakened or dead trees? Probably because their eggs cannot survive in healthy trees which employ the usual chemical strategies to rid themselves of pests. Many elm protection programs target the beetle; basal spraying, to kill off populations of H. rupifes, for example, but this strategy is not all that successful as the number of infected beetles is actually quite small.

8. Prevention and protection. The number one preventative measure is to keep your tree healthy and to prune off any dead or dying branches 10 feet below symptoms. Do this in winter when the beetles are inactive. Do not, under any circumstances, store elm wood, because it creates breeding places. And don't transport elm wood, either. Don't allow your trees to be weakened by drought. Water them when they need it and be generous. Water deeply, knowing that their feeder roots are likely in the top eight to 12 inches of soil, especially in clay-based soils. Occasionally, give your elms a good feed of mycorrhizal fungi and fertilizer. Healthy trees can muster their own resources to fight off the fungus.

9. Even more resistant elms. Scientists have been working to develop resistant trees for years. They have come up with the Liberty elm, Brandon elm (not vase-shaped) and the Independence elm to name a few. However, the fungus has also been at work, mutating to protect itself. A very virulent strain called Ophiostoma nova-ulmi has been at work for a number of years.

10. Other elms. At one point in some cities that had lost their elms, the weedy Chinese elm ( Ulmnus parvifolia) or lace bark elm, and the Siberian elm ( Ulmnus pumila) were planted as being resistant to the disease. Both are fairly invasive and both are susceptible to Dutch elm disease. While Siberian elm is not as quickly killed by the disease and shows fewer symptoms, it can be a vector, infecting beetles that then spread the disease to American elms. Chinese elms are more resistant, but can harbour the disease as well.

Copyright© Pegasus Publications, Inc.

Dorothy Dobbie is the author of 10 Neat Things, published by Pegasus Publications and is a new contributor to KBR.